If you love skiing and good food ... Thank Gretl

From German ski racer to Aspen's Queen of Strudel, Gretl Uhl has shaped her own life Gretl Uhl's affairs are in order and she is heading to Hawaii for two weeks of beach time, to swim in the warm water, smell the tropical flowers and visit with new and old friends. Doctors in Houston have suggested that the cancer she is battling is a fierce and determined foe. But what do they know about stubborn German women who love life and are used to getting what they want? At 77, Gretl's blue eyes still flash brightly and her bouncy laugh rises as easily as ever, even when discussing alternatives to chemotherapy. She can laugh, almost giggle really, when saying, in her lilting accent, how she is now more determined than ever to embrace and enjoy life every day, despite the fatigue and the incessant pain. If you didn't know about her illness, you wouldn't know, for being in Gretl's presence is still like soaking up the warmth of the sun, like spending time in a field of flowers with a young girl, like being in the kitchen just when the chocolate birthday cake is pulled from the stove.  And if you are lucky enough to hear her ask one of life's sweetest

questions, "Are you hungry?" then you must answer "Yes" and sit yourself

down in her warm, cozy kitchen for some soup, some cake, and plenty of

sumptuous fare in between. And if you are lucky enough to hear her ask one of life's sweetest

questions, "Are you hungry?" then you must answer "Yes" and sit yourself

down in her warm, cozy kitchen for some soup, some cake, and plenty of

sumptuous fare in between.

Gretl's life story is the stuff of novels, of grand sweeping reviews of history. And her energy, warmth, charm, determination and full embrace of life and good food have endeared her to generations of Aspenites. A native of the Bavarian Alps, her young life was shaped by mountains and skiing, by the 1936 Winter Olympics and then by World War II. Arriving in Aspen in 1953 with her husband, Sepp, she taught skiing on Aspen Mountain until 1966 when she opened Gretl's restaurant in Tourtelotte Park, where Bonnie's is today. For the next 13 years, Gretl's became the place on Aspen Mountain for hippies and movie stars, eager visitors and hard-core locals ... for skiers of all stripes to gather for sunshine, homemade food and sweet, light apple strudel with thick whipped cream.  She set a new standard for what is now often called "on-mountain dining"

and the memory of her strudel, the fresh dough rolled out each morning on

a small table in a crowded kitchen, lingers on in many a ski bum's memory. She set a new standard for what is now often called "on-mountain dining"

and the memory of her strudel, the fresh dough rolled out each morning on

a small table in a crowded kitchen, lingers on in many a ski bum's memory.

Last November, her loyal former employees from Gretl's threw a surprise reunion for her. The crew filled the Steak Pit restaurant with laughter, stories and some tears. And no doubt their tales of the late '60s and the long-lost '70s could now fill a book of their own. So there is a much larger, more detailed story to tell, still to come. But Gretl was open this week to the idea of sharing some of the highlights of her life with us. Before she opened her photo albums and a fraction of her meticulous archives, she suggested reading a book by Meredith W. Ogilby called "A Life Well-Rooted." It's a collection of short profiles of women in the Roaring Fork Valley with photographs by Ogilby. Gretl's picture, appropriately, was taken in the kitchen of her 1898 Victorian on West Hallam Street in Aspen. Ogilby writes that "flavored by Bavarian design, the interior of Gretl's house is a gallery of handicrafts. All the cabinets in her kitchen, the chest in the living room and the chairs around the hospitable kitchen table were beautifully hand-painted by her husband, Sepp. "Although there are many details to divert your attention, photos of Aspen's earlier days, works of art and knickknacks, you are pulled by the allure of the kitchen; it will fuel your soul. "With a sweep of her hand, gathering the years, Gretl pronounces, "You wouldn't believe the people who have sat at this table, rich, poor, famous, small ...' It doesn't demand such a stretch of the imagination, for no matter who you are you feel welcome and are immediately engaged in amicable conversation." Here then, is a glimpse into Gretl's life, and it's offered in the same spirit of warmth, humor and zest for living that Gretl loves to share, now more than ever, with anyone she meets. A successful restaurant Gretl Hartl was born in 1923 in one of Aspen's sister cities, Garmisch-Partenkirchen in the Bavarian Alps, south of Munich and just north of the Austrian border. It's a stunningly beautiful resort town and is home to Germany's tallest mountain, the Zugspitze. There are two little towns split by a river in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, and Gretl was distinctly from the more upper-crust Partenkirchen side of town. She and her sister grew up with a maid and nannies, and her parents went out often at night to dinner and to parties. As a young girl she learned just a touch of English, and can still recite "early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise" in the hesitant cadence of a school girl who learned it by rote.  Gretl's father was one of the founders of the ski club in town and Gretl

was comfortable on skis by the time she was 6. Her mother was not a skier.

She ran a restaurant called Cafe Hartl.

Gretl's father was one of the founders of the ski club in town and Gretl

was comfortable on skis by the time she was 6. Her mother was not a skier.

She ran a restaurant called Cafe Hartl.

"Everything was good, everything was fresh," Gretl remembers. "I loved to be in the kitchen, but we were always chased out of it. My mother ran a good place. She was such a good organizer." The restaurant was located in a typically Bavarian, two-story building built in 1923. In 1935, an Olympic ski-jumping stadium was built right next door to the restaurant in anticipation of the 1936 Winter Games, to be held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. The restaurant's location was great for business. "It was between the parking area and the stadium," Gretl said. "The people had to fall into it." The police had to help manage restaurant seating during the Olympics. People filled up the restaurant, ate and then left out the back door as a new group was ushered in the front. Gretl's mother rented out the yard behind the restaurant to a group serving chicken-on-a-spit and the upstairs balcony, with its view of the stadium, was rented out to movie stars. "And she charged them an arm and a leg," Gretl said. "For her, money was everything, and she was smart." Love, and war Gretl's mother played a big role in her life. She was very proper, very strict, and expected Gretl to conform to her idea of proper behavior. "It was so drilled into me and my sister, that we will never be touched by a man until we are married," Gretl said. "And believe me, I lived that 100 percent. People won't believe that because I was such a flirt. I loved to dance. I liked to have a good time. But, for me, it was just plain 'no. Gretl had plenty of prospects for romance with the boys from her small town, but as the dark shadow of Nazi rule and World War II was cast over Garmisch-Partenkirchen, that changed. In 1939, her parent's restaurant was confiscated by the Nazis. "Bavaria was anti-Nazi and the Gestapo was everywhere," Gretl is quoted as telling Jim Kahnweiler in a 1979 Aspen magazine article. "They were afraid of sabotage and armed resistance from us and made everyone turn in their skis. But everybody had a more than one pair, so we turned in our worst and hid our best. The regime neglected us and several winters we ate only potatoes and bread." Worse, all of the 30 men in her high school class went away to war and only eight came home. "I lost somebody I really, truly loved," Gretl said. "He was killed in Russia. And then somebody else was on a U-boat and didn't return. I knew a lot of them. It was very hard to lose somebody." She distinctly remembers the day the Germans were defeated by the Russians at Stalingrad. It was Feb. 4, 1943, and the Germans were driven back after a brutal two-year siege. "I had friends there who I was in contact with," said Gretl. "And they were all encircled. It must have been absolutely a horror." In 1943, at age 19, Gretl was drafted by the Nazis. "We had a choice," she recalls. "I went to the railroad office where I did the payroll." Asked if having been German in World War II is hard today in America, Gretl says no. "That's history. Simple as that." After the war, the occupation by American soldiers began. They took Gretl's childhood home as their regional headquarters. And Gretl, looking back, describes a romantic scene tinged with the gritty realities of the time. In June 1945, she was still working at the railroad station in Garmisch, doing the payroll. "I was the only girl in the office," Gretl said. "Here was an American officer. Every morning he was sitting at the stairs going up to the hall of the office. He was reading his American newspaper, but actually waiting for me to appear. He would look over his newspaper and say 'Good morning, Fraulein Hartl.' "He had absolutely and deeply fallen in love with me. And I liked him too; he was a tall, good-looking guy, but because he was an American, there was a wall." His name was Edward Matusik. From Highland Park, Ill. "When he had to leave, he gave me his address," Gretl sighs. "And that address is just burned in my brain. And I never heard from him again." Nor has she ever tried to contact him. And the war, and Garmisch's role in it, would continue to shape Gretl's destiny.  Turns of fate Turns of fate

The American military in Germany could clearly see Garmisch was a beautiful resort, and an American recreation center was set up to give soldiers from all over Europe some rest and relaxation, including skiing lessons. At the time, Sepp Uhl was a certified ski instructor at the recreation center, which still exists today under the name of the Armed Forces Recreation Centers in Europe. Gretl was a ski racer, a member of the German National Team, and she jokes that she always came in second place. "I was supposed to compete in the 1948 Olympics," she told The Aspen Times in 1980. "But they were canceled. We were still close to the war." But through the common ground of the ski slope, Sepp and Gretl met in 1947 and were married in 1948. "Sepp had something special," Gretl says. "He was a true gentleman. He was good-looking and full of life. He could sing and entertain close friends and family. He was never bored and always had something going."  Sepp may have been a handsome, intelligent and charming man, but he was

also the brother of the maid who had worked in Gretl's house. Sepp may have been a handsome, intelligent and charming man, but he was

also the brother of the maid who had worked in Gretl's house.

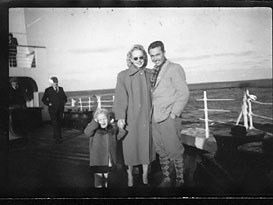

He was from Garmisch, not Partenkirchen, and Gretl's socially rigid mother never welcomed him into the family. Later, in a wedding album richly illustrated by Sepp, who was a talented artist, his mother-in-law was slyly depicted as a three-headed dragon. As fate would have it, Sepp had once gone to school in Germany with the young Dick Durrance, who would become a top American ski racer, a competitor in the 1936 Olympics and, in 1947, the first general manager of the Aspen Skiing Corporation. In February 1950, the FIS World Championships were held on Aspen Mountain. In 1951, Durrance traveled to Europe with a film he had made about the races. "We were invited to a showing of Dick Durrance's movie," Gretl recalls. "We saw the movie and wished we could ski there." And Tony Woerndli, who was best man at Sepp and Gretl's wedding, was already working for the Aspen Ski School under the direction of Friedl Pfeifer. Tensions with Gretl's mother continued to escalate and Aspen looked increasingly attractive. So Sepp and Gretl went to the American consulate in Munich to fill out the necessary paperwork to move to America. "My parents were to give us the money to move, but when the time came in July of 1953, they retracted the offer," Gretl remembers. "The man who ran the ski school in Garmisch lent us the money to come."  On to Aspen On to AspenThe couple sailed from La Harve, France, to New York City and took a train to Denver and then to Glenwood Springs. They arrived in Aspen in November 1953 and stayed with Woerndli at the Alpine Lodge on Cooper Avenue. They then rented a house from Judge Shaw and his wife on Main Street for $45 a month, and Mrs. Shaw allowed them to work off part of the rent for a $1 an hour doing repairs around the house. The house, flanked by two other small houses, still stands on Main Street. One of their neighbors was Kurt Bresnitz, who for years ran a jewelry store in Aspen. The other neighbor was Freddie Fisher, noted musician, character and soon-to-be Aspen legend. Gretl said she felt welcomed by the Aspen community right away. "It was so neat," Gretl says. "We met Red Rowland and all these people right away. And when they had a big dance at the Grange Hall, which is now City Hall, they invited us right away." Sepp took a position with the ski school, which mustered all of 17 instructors that Christmas. He would go on to become ski school supervisor in the 1960s. In 1955, Gretl also became an instructor. She would teach on Aspen Mountain for a decade and she became one of the top instructors on the mountain. "I was group leader for the instructors," she said. "I taught them all how to teach. I had big groups before the season started. I got people ready for the clinics." When asked if the years in Aspen from 1955 to 1966 were good ones in town, with lots of powder and lots of good cheer at the Hotel Jerome, Gretl's eyes just twinkle. "I loved it," she said. "I absolutely loved it. It was really special." In 1957, she had approached Walter Paepcke, the industrialist from Chicago who had financed the start of the Ski Corp., founded the Aspen Music Festival, and bought a score of empty Victorian houses in town.  Gretl had spotted a house on Hallam Street that she wanted, that she, in

her stubborn way, just had to have. Paepcke told her he'd give her a

second mortgage if she could secure a first mortgage. Gretl had spotted a house on Hallam Street that she wanted, that she, in

her stubborn way, just had to have. Paepcke told her he'd give her a

second mortgage if she could secure a first mortgage.

"Albert Duroux gave us the first," she said. "He was the janitor for the Hotel Jerome and he made the best Italian wine. And he owned a whole property on the lower part of Red Mountain." Gretl still lives in the house in the West End and has begun a crusade for property tax relief for longtime residents like her who don't want to sell and reap the benefits of Aspen's surreal real estate prices. She thinks people who just want to live in their houses shouldn't be penalized because the houses around them have turned into investment properties. But it certainly wasn't always a sure bet that Aspen's West End would amount to much. Nor was Gretl sure at the time that trying to support her family on the salaries of two ski instructors was such a good idea, especially as by now she and Sepp had two children, Renata and Tony.  An insistent idea An insistent idea

One day in February 1966, while standing at the ski school meeting place, she impulsively decided to act on a long-simmering idea. If the Aspen Skiing Corporation decided to build another restaurant on the mountain, Gretl wanted to run it. At the time, there was just one restaurant - the Sundeck, at the top of the mountain. "It hit me like fire," she recalls. "I excused myself from ski school and ran into Darcy's office." That's Darcy as in DRC Brown, the tall, somewhat intimidating former president of the Aspen Skiing Corporation. Gretl had no appointment. No proposal. Just an urgent idea. "He said something to the affect, 'Couldn't this wait until this afternoon?' Gretl laughs. But it couldn't. Gretl told him she wanted to run the company's next on-mountain restaurant. "The only thing he said was 'Well, what experience do you have?' I said I had grown up with it. But I didn't tell him I never thought that I would do that in my whole life." In June of that year, Brown called Gretl and they drove up to Tourtelotte Park, where the Ski Corp. was building a small warming hut. And that's what they offered Gretl. "The first lease I didn't accept," she said. "They wanted me to be only a warming hut with hot chocolate and tea and maybe some sandwiches. And they wanted to pay me less than a ski school supervisor." But a deal was worked out and on Oct. 6, 1966, the company issued a press release from A. G. Bainbridge, the director of marketing. "Gretl Uhl, for eleven years with her husband, Sepp, mainstays of the Aspen Ski School teaching staff, will open a new restaurant on Aspen Mountain," the release began. "This cozy alpine hut is directly over an old mine in Tourtelotte Park and will be entirely 'manned' by housewives of Aspen." Gretl did round up 22 housewives and friends to help her launch the restaurant and there was one man among them. But only one. "I'll never forget the first day we opened," Gretl told The Aspen Times in 1980. "Our customers came in, looked around, and said ... it looks like PTA. I had hired all my friends." Gretl said the Ski Corp wanted the new facility to take some pressure off the crowded Sundeck, but apparently not too much. She said she was given no advertising budget and directional trail signs to the new restaurant were not posted. "We just opened our windows and the smell went right to the lifts," she said. "You wouldn't believe how good it smelled."  A new approach to lunch A new approach to lunchFor Gretl had decided to do more than serve hot chocolate and hamburgers. "My whole aim was to change the food at on-mountain restaurants," she said. "It was all out of cans and hamburgers and hot dogs. The Sundeck had a good salami sandwich. He had good quality. But it wasn't anything made. And it wasn't anything catered to the people. You always had pea soup or chicken noodle soup. There was no change. It was boring." Gretl's menu was part Bavarian and part American. She always had homemade soups and fare such as cabbage rolls, stuffed peppers and beef roulade. And there were always scrumptious desserts like fresh cream puffs, gingerbread and fresh strawberries. But not, at first, strudel. For the strudel to become a staple on the menu, and then become the dessert that would make Gretl famous, her employees had to try it. "One day, we had such a snowstorm and the lift was closed and we were up there," Gretl said. "When we were up there alone, we always made a party. So I said, 'I tell you something, here are the apples, I make the dough, I make you something good.' I made a strudel for them and they said, 'This would be a hit. Why don't you make it? The strudel craze was born. At one point in the late 1970s, Gretl was going through 200 cases of apples in three months to keep up with demand.  And Gretl's Tourtelotte Park Restaurant became a hit. A deck was added

on. The kitchen was expanded. And the restaurant became the most important

meeting place on Aspen Mountain for the newest group to come to town, the

hippies.

The national media began to take note of both the young people and the

strudel.

And Gretl's Tourtelotte Park Restaurant became a hit. A deck was added

on. The kitchen was expanded. And the restaurant became the most important

meeting place on Aspen Mountain for the newest group to come to town, the

hippies.

The national media began to take note of both the young people and the

strudel.

In 1974, Ski magazine noted that Aspen had "an abundant counterculture, represented by long hair over very short skis" and called Gretl's "the best cafeteria in American skiing." It also said, without irony, that the food at Gretl's was "not cheap. Soup 60 cents, burgers $1.15. Save 75 cents for the strudel." By 1976, prices had gone up. Women's Wear Daily that year called Gretl "the strudel maven" and wrote that "if the Rockies feed the soul, people like Gretl make sure of the stomach. A hunk of her strudel is $1 and it is so sublime there are people who feel their trip to Aspen is wasted if they miss out on it." In 1980, Town and Country magazine ran a big feature on Aspen and included a full-page photo of Gretl, dressed in her apron, holding up a plate of strudel. She was called the "beloved proprietress of THE lunchtime meeting place for Aspen's most glamour skiers." And Gretl was beloved, by both celebrities and her employees. On the job, she got to know the big names like George Hamilton and Jack Nicholson. "You know who was so nice to me?" Gretl asks. "Jack Nicholson. When he came up he always made me sit down. He would come in a little later, around 2:30, and he would say, 'You haven't had your tea and rum yet, have you? Come on, get it.' "And we were sitting there. And I have really heard so much about his private life because of it, and I really got to like that man. He was simple, uncomplicated. He always said, 'You won't believe it, but I don't fit into Hollywood. I am the black sheep there.' We became really good friends." And she remembers an unruly mob of Kennedy kids in the early 1970s who would sit around and throw food and get in trouble, looking for attention. So Gretl gave it to them and put them to work in the restaurant. "I assigned each child to one of my employees," Gretl said. "They carried stuff up. They did everything. Gosh, they were miserable. But they were only bored." She had less kind words about Ted Kennedy. "I didn't like Ted Kennedy," she said. "I had a few run-ins with him. We had only one telephone and we needed it so much. He would not ask. He would just go through the kitchen to that telephone. And there was just that small little space from the kitchen to the serving line. And he is big. And he sticks his behind out and there was no way around there." Gretl asked him to stop using the phone. "And he was not nice. He said, 'We will go up to the Sundeck,' and I said, 'That's OK with me. The Queen's Court But a big part of the magic of Gretl's was her staff of 36 employees. She may have started the restaurant with the help of 22 housewives, but she eventually hired ski bums and hippies to cook the food and bus the tables. She was famous for paying well, feeding her employees even better, and holding big wild parties the day after closing for the season. Notable local veterans of Gretl's include PJ of Backdoor Catering, who was a busboy for Gretl and ended up working for her longer than anybody else. And it was PJ's margaritas, Gretl said, that made sliding on cafeteria trays from the top of Ruthie's Run down to the restaurant so much fun. Loren Ryerson, now a veteran of the Aspen Police Department, was a busboy at Gretl's, as was his brother Ned. And bussing at Gretl's was Rob Baxter's first job in town. He would go on to become mountain manager on Ajax and then at Snowmass. And there are many, many others, all of whom deserve more notice than space allows here. One reason that working at Gretl's was so appealing, in addition to the food, was the two-days-on, two-days-off schedule that she pioneered. It is a perfect schedule for anyone who hates to work. "Because I am skier and I know that two days you can work if you know the next two days are yours," Gretl said. "Or if they wanted to go to Snowbird, there was always this alternate crew, and if I knew it, they could go, because they would say 'I work for so and so.' And because of it, I had no trouble on weekends." Today, most local mountain restaurants that still hire skiers use the two-days-on, two-days-off schedule.  And Gretl was famous for working with, not above her employees. She

worked seven days a week all winter long, taking the first chair up at

7:45 a.m. and skiing down off the mountain through Spar at 4:30 p.m.,

which is a dark and cold time in midwinter. And Gretl was famous for working with, not above her employees. She

worked seven days a week all winter long, taking the first chair up at

7:45 a.m. and skiing down off the mountain through Spar at 4:30 p.m.,

which is a dark and cold time in midwinter.

Her shoulder-to-shoulder work routine once caused her some heartburn from the homeland. "I remember a lady who came over from close to my hometown," Gretl said. "When she came in, she knew my parents, and I was in my apron, I was working. She said she was so disappointed that as a manager that I run around like my employees. "'Well,' I said, 'You are in the U.S., you are not in Garmisch.' I told her that if I am not such a good example to my employees, I wouldn't have such a good place. She thought I should be dressed nicely and go around and greet everybody and talk and not know what was going on back there in the kitchen. And instead, it was the opposite, you know." Gretl knew exactly what was going on in the kitchen. And she knew if people were moving a little slow in the morning. "If they had hangovers, they had to drink the cup," she laughs. "They had to drink 8 ounces of warm water with two tablespoons of apple cider vinegar in it. Believe me, in two hours there was no headache. I saw they had a hangover and I would say 'Your cup is ready.' "And I would make them eat raw sauerkraut. Just maybe two tablespoons full to stay healthy. I did it myself. Believe me, I didn't have a sick crew." In 1979, Jim Kahnweiler wrote in Aspen Magazine of his experience working for Gretl, saying that "I had no idea at the time, but Gretl's Restaurant was the best job I've ever had. Unlike other restaurants, Gretl has a vast choice of people who want to work for her and she can be very choosy. Everyone working at Gretl's is a skier and there is a certain camaraderie among the employees. And I quickly learned that no one works for Gretl, he works WITH her." End of an era So it came as a shock at the end of the 1979-80 ski season when Gretl announced that she would not be signing a new lease with the Ski Corp. and that she was done serving strudel. The headline in The Aspen Times read "Gretl won't be standardized ... she'll quit." The story, written by Mary Eshbaugh Hayes, was to right to the point. "Aspen Mountain will never be the same. "Because Gretl's Restaurant won't be there anymore. "Gretl is not a quitter. We all know that if she could have gotten over the problems with hard work ... that's what she would have done. "Because she has always been a dynamo. Her energy and tenacity are as famous as her strudel." The charge of being "standardized" came as the new owner of the Aspen Skiing Corp., 20th Century Fox studios, was applying a new corporate approach to operations. Gretl's new lease required her to get her own snowcat to transport food to the restaurant, as other on-mountain restaurants had to do. And they wanted her to pay to maintain the building, even though the Ski Corp. owned it. For Gretl, the decision to reject the lease offered by the Ski Corp. was a tough decision, and one that she had felt was in the works for some time. "I was nearly sick," she said this week. "It took me two years to go back up on the mountain. It hurt me so much. I was close to a breakdown. They wanted me to get out of it without having the guts to say so and to say why. It was too much competition for them. I couldn't understand and nobody explained to me why they wanted me out, and I still don't know to this day." But Gretl has a hunch the seeds of her exit were planted high up in the 20th Century Fox organization. " There was a funny incident," she remembers. "When 20th Century Fox took over, Mr. Stanfield came up with his family and secretary. I must say he was very charming and nice, but his secretary, I can only call her a bitch. There was such a dislike coming from her. And seeing a woman successful, German to boot, it just didn't go over. "And that's when I felt the first things develop. And then little things coming from their side. If I was to have known that Marvin Davis took over, I would have held out. Ethel Kennedy was such a close friend of Marvin Davis, and she was the one who said 'Hold out, we'll get you through this.' But I was so hurt that they gave me a lease that I couldn't accept. I would have been stupid to accept it." And so an era passed. She waved off offers to go to Park City. To Telluride. To Deer Valley. To start a franchise. In 1982, Gretl signed on as a consultant with George Schermerhorn and Robert Cronenberg to help them run the Merry-Go-Round restaurant midway at Aspen Highlands. And they still serve Gretl's strudel, although the dough has not been rolled out by hand by Gretl on a small table in the back room and the apples don't come from Paonia in the back of her station wagon. But it's still good, especially when eaten with fresh whipped cream, outside on the deck as skiers streak by.

Her son, Tony, daughter-in-law, Leslie, and two grandchildren, Sage and Griffin, live in Emma. Her daughter, Renata, lives in Grand Junction. Gretl's kitchen is still a warm and busy place, full of friends dropping by for tea and the answering machine picking up long messages from people whose German is better than their English. Her grace and style, formed all those years on the mountain as a ski instructor, are still intact. She enjoys volunteering as an ambassador for the Aspen Skiing Company on Aspen Mountain and was recently named Winterskol Queen. Her determination and willingness to take risks, which were forged as a successful businesswoman, are still evident in her approach to her current challenge. And the God-given Bavarian blush of her cheek, and intense sparkle of her eyes, still radiate like the sun off the snow on a March afternoon in Tourtelotte Park. Brent Gardner-Smith Reporter Aspen Times PH: 970.925-3414, ext. 230 News Room After Hours: 970.925.3689 FX: 970. 925.9156 bgs@aspentimes.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|